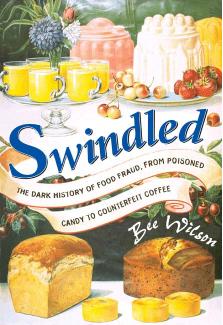

Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee by Bee Wilson

Author:Bee Wilson [Wilson, Bee]

Language: rus

Format: epub, pdf

Tags: aVe4EvA

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2008-07-09T20:00:00+00:00

5

Mock Goslings and Pear-nanas

Today we don’t have anything so crude as adulterants; we have additives and improvers and nutrients.

—Elizabeth David, English Bread and Yeast Cookery (1977)

George Orwell was a child during the First World War. When he looked back on his early life, he confessed that his chief memory was not of all the deaths, but of all the margarine. The butter shortages caused by the Great War meant that margarine switched from being the food of the poor to being a universally used substitute—even for privileged scholars at Eton, such as Orwell. “By 1917, the war had almost ceased to affect us, except through our stomachs.”1 Orwell, in his clear-eyed way, saw how food was increasingly being reduced to a kind of unfood. He abhorred this “century of mechanization,” which had, he believed, more or less eliminated the “taste for decent food.” Thanks to tinned food, “synthetic flavouring matters, etc., the palate is almost a dead organ.”2 In Orwell’s novel Coming Up for Air, the hero George Bowling (who is reduced to eating fake foodstuffs such as fish frankfurters or artificial marmalade) complains: “Everything comes out of a carton or a tin, or it’s hauled out of a refrigerator or squirted out of a tap or squeezed out of a tube.”3 Orwell himself lamented the decline of the English apple:

As you can see by looking at any greengrocer’s shop, what the majority

of English people mean by an apple is a lump of highly coloured cotton

wool from America or Australia; they will devour these things, apparently with pleasure, and let the English apples rot under the trees. It is the shiny, standardized, machine-made look of the American apple that appeals to them; the superior taste of the English apple is something they simply do not notice. Or look at the factory-made, foil-wrapped cheeses and blended butter in any grocer’s; look at the hideous rows of tins which usurp more and more of the space in any food shop, even a dairy; look at a sixpenny Swiss roll or a twopenny ice-cream; look at the filthy chemical byproduct that people will pour down their throats under the name of beer. Wherever you look you will see some stock machine-made article triumphing over the old-fashioned article that still tastes of something other than sawdust.4

Orwell wrote these words in 1937. About this, as about so much else, he was prophetic. The world of synthetic food that he described so potently was only just beginning. Orwell was right that the twentieth century would be the century in which fake foods became the norm. He was also right that while these fakes started off as shabby substitutes—the reviled margarine of the Great War—they soon became seen by many as superior alternatives to the real food they replaced. By the old standards, this squirted, cartonned, squeezed food would have counted as adulterated. But as the century progressed, tastes and norms changed. The “shiny” and the “standardized” came to be prized above the real.

Ersatz Food and Wartime

Download

Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee by Bee Wilson.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15293)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14463)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12352)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12072)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12001)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5740)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5408)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5382)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5283)

Paper Towns by Green John(5160)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4981)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4474)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4472)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4423)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4370)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4319)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4298)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4167)